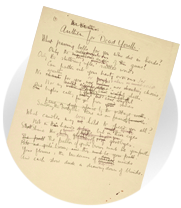

Anthem for Doomed Youth manuscript

Britten corresponded with Harold Owen, the poet’s younger brother, following the premiere of War Requiem. The composer sent him a signed first edition of the score and on 25 April 1963 Harold reciprocated by sending Britten two extraordinary gifts. One was photograph of a very young Wilfred taken while he was a student in Dunsden in about 1912. The other was a well-worked manuscript in the poet’s hand of Anthem for Doomed Youth, or Dead Youth as the draft originally had it.

‘… I am sending you this manuscript draft of Anthem for Doomed Youth in gratitude for your superbly beautiful Requiem. It is interesting—I think—because it shows so clearly how Wilfred worked, writing many drafts before he attained what he wanted to say. I know that Wilfred never ‘laboured’ on his poems but he did—in the true sense—work very hard on everything he wrote.

As you know nearly all Wilfred’s manuscripts are in the B.M. [British Museum] so I am particularly pleased to have this early draft of a poem you used in the Requiem to give to you…

With every good wish

Yours sincerely

Harold Owen

The manuscript is undated, although we know that it was written in late 1917 while Owen was still a patient at Craiglockhart Hospital. The redrafting process, to which Harold makes special reference in his letter, was a significant part of the process of composition. Owen received some guidance in this respect from Siegfried Sassoon, as is indicated in the following passage from Pat Barker’s Regeneration, the first in a trilogy of novels that provides a partly fictionalised account of Owen’s treatment at Craiglockhart and his experience during the war.

‘What draft is this?’

‘Lost count,’ Owen said. ‘You did tell me to sweat my guts out.’

‘Did I really? What an inelegant expression. “What passing bells for those who die as cattle?” I see we go to the slaughterhouse in the end.’ Sassoon read through the poem. When he’d finished he didn’t immediately comment.

‘It’s better isn’t it?’

‘Better? It’s transformed.’ He read it again. …

[Sassoon] looked down at the page. ‘I think you should publish this.’

’You mean in the Hydra?’

‘No, I mean in the Nation. Give me a fair copy and I’ll see what I can do. You’ll need a different title, though. “Anthem for …”’. He thought for a moment, crossed one word out, substituted another. ‘There you are,’ he said, handing the page back, smiling. ‘”Anthem for Doomed Youth”’.

From Pat Barker, Regeneration (London: Penguin Books, 1991), Part 3, pp.156-8

The draft copy of Anthem for Doomed Youth reveals a number of significant differences between Owen’s initial thoughts and the finished text. One of the most striking of these is that the poet’s voice was more direct in the earlier version, appealing to his fellow soldiers and to the spirits of the fallen. Altered phrases indicate that Owen’s speaker originally stressed the tragedy by remarking on the passing bells ‘for you who die in herds’, the rifle fire pattering ‘out your hasty orisons’, and bugles that ‘call for you from sad shires’. In the final version, however, the personal pronouns are removed and the voice is more detached and authoritative, emphasising the harsh reality that young men are seen as easily expendable and led to slaughter like cattle rather than as human beings. Owen’s point is to raise the reader’s awareness of the link between the brutality of warfare and the suffering endured on the battlefield. The manuscript, full of the sentiment of the pity of war, was prized by Britten and is still kept in the composer’s archive at The Red House in Aldeburgh.

© Britten-Pears Foundation

© Britten-Pears Foundation © Britten-Pears Foundation

© Britten-Pears Foundation